Professor and Author Robin Wall Kimmerer Delivers Talk on Environmental Justice

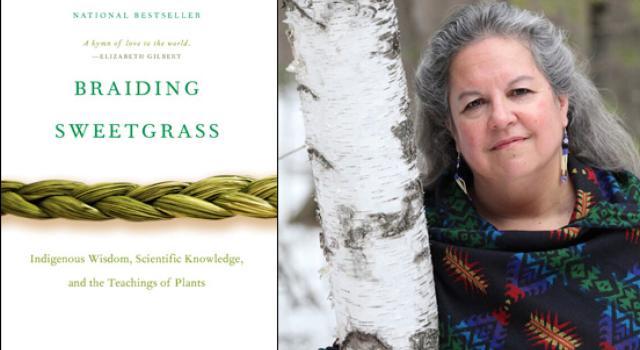

The professor of environmental biology and author of the bestseller Braiding Sweetgrass, which was the College’s Common Read for the 2023-24 academic year, spoke to the community about the book’s critical themes as well as what her vision of land justice might look like.

On February 13, to both an in-person audience in Franklin Patterson Hall and a virtual audience on Zoom, Kimmerer explored Indigenous perspectives about land conservation, from biocultural restoration to the Land Back movement. Full of more provocative questions than answers, her presentation invited the Hampshire community to consider how engaging in traditional ecological knowledge contributes to justice for land and people.

Introductions were by Andrew S. Yang, Jonathan Lash Endowed Professor of Environmental Studies; and Amy Jordan, associate professor of African American history. Assistant Professor of Native American and Indigenous Studies Noah Romero then presented a land acknowledgment, noting the need for us to move beyond a mere acknowledgment to decolonizing education and elevating Indigenous education.

Kimmerer opened her presentation — “What Does the Earth Ask of Us?” — by grounding the attendees in gratitude. After all, she pointed out, “Our lives are made possible by the earth.” She also asked them to think about living in such a way that one day the earth would be grateful for us. “How do we enter a reciprocal agreement with the living world?” she asked.

Looking at common definitions of sustainability, Kimmerer suggested reframing the entire concept so that we consider not simply taking from the earth, but also integrating ways of giving back — thinking of ourselves not as consumers only, but how we might have a positive impact on ecology.

Western ideas about land have been rather narrow, she says, and include treating it as property and/or capital, offering “ecosystem services,” such as oxygen and fertile soil, and natural resources, like raw materials. In contrast, her Indigenous upbringing taught her that land is a source of identity, a home for humans and non-humans, a teacher (source of knowledge), and a healer (source of medicine), as well as intrinsically valuable and sacred.

She asked more of those listening: “How has your worldview been colonized? What are the consequences? What are you going to do about it?”

Kimmerer referenced a sobering recent United Nations report about biodiversity loss all over the planet, but mentioned a bright spot: there are places where biodiversity is thriving — Indigenous ones. Eighty percent of the world’s remaining biodiversity is safeguarded by Indigenous peoples, though they have only 10 percent of the land rights. “Humans aren’t necessarily negative influencers,” she said, “but we have to participate in the care and protection of cultural diversity that supports this.”

Addressing the ways settler colonialism attempted to replace ways of life, language, knowledge, and worldviews, as well to take the actual land, Kimmerer continued, “This must be grieved and healed.” She described the Anishinaabe concept of justice, which addresses harm that has been inflicted, focusing on the relationships between offender and offended in the spirit of restoring balance through personal and social healing — that is, the notion of restorative justice.

Justice for the land might look like repatriation, restoration, protection of cultural areas, and engagement with tribes in meaningful collaborations, she said, reflecting on going beyond mere acknowledgment. And she touched on Land Back, a movement to get land back into Indigenous hands.

In her presentation, Kimmerer showed a slide featuring a graphic of a pair of eyeglasses. Each lens represented a unique perspective: one lens for Indigenous knowledge and the other for Western science. Kimmerer emphasized the importance of integrating these views: “Seeing with both eyes. That is our work,” she said.

After her lecture, Kimmerer took questions from students and faculty. You may watch the full event here: