Designing for a Purpose

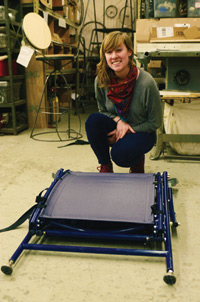

Katie Coupe learned of the exam-table project after taking the January term course in El Salvador, and decided to get involved.

Evolution, whether natural or technical, is rarely a one-step process. Most of the time it's not a one-person process, either. Collaborative skills, mistakes, and inspiration keep a good idea going until it becomes a working reality.

Evolution, whether natural or technical, is rarely a one-step process. Most of the time it's not a one-person process, either. Collaborative skills, mistakes, and inspiration keep a good idea going until it becomes a working reality.

Take the portable gynecological exam table, for example.

That Hampshire project began with Emily Ryan. She had gone to El Salvador in 2009 as a student in the January term course Field Study in Women's Health, which was led by Associate Professor of Public Health Elizabeth Conlisk and Hampshire alum Miriam Cremer.

Cremer, an obstetrician and gynecologist, is the founder of Basic Health International, a nonprofit focused on eradicating cervical cancer in El Salvador. She contacted Conlisk about starting the course to get students involved in the cervical cancer screening work, and the professor quickly agreed.

"At Hampshire, fortunately, I have the freedom as a faculty member to act on good ideas. I didn't have to go through a long approval process to go ahead with this," says Conlisk.

Ryan found herself accompanying physicians into rural villages where cervical examinations were done without the high-tech equipment or surroundings of a typical diagnostic setting in the United States. She realized that an examination table doctors could carry with them—through terrain sometimes too rugged for anything but travel by foot—would make their jobs easier and the procedure more comfortable for the women.

"I wanted to help in any way I could," says Ryan. "The next semester I did an independent study, brainstorming and working with other students on the design."

Says Conlisk: "We thought there was a real need for this. We looked online for a portable gynecological table, and there was nothing on the market."

The first prototype, made in Hampshire's Lemelson Center for Design, was tested during another trip to El Salvador, and the two women saw that the table had to be lighter, sturdier, and easier to carry. They also questioned whether plans to make the tables out of easily acquired materials, so they could be made by El Salvadorans wherever they were needed, was the best approach.

"The first bed was made of steel conduit and slit bicycle tires," recalls Conlisk. "It wasn't the most elegant-looking thing, and it probably wasn't as well received as something more polished would have been."

That's where Katie Coupe came in.

Coupe learned of the exam-table project after taking the January term course in El Salvador, and decided to get involved. "I had been working in Lemelson, and because we have access to this technology and these tools, we can design things that benefit people. I thought I could help redesign it: make the bed more portable and robust," she says. "Then we had the idea to make it into a backpack, so it could be more easily carried."

When Ryan graduated, Coupe essentially became the leader of the project. Next came an important addition to the team in Aaron Cantrell, whose experience in design led to several breakthroughs for the table's overall look and choice of materials.

He, Ryan, and Coupe came to the conclusion that manufacturing the beds in El Salvador wasn't practical, so they started from scratch on a model based on Ryan's experiences. They also tested whether it could be manufactured elsewhere and shipped at an affordable cost to El Salvador.

The Hampshire students have been able to create and test the gynecological-examination table prototypes thanks to the financial support of Basic Health, which is excited about the potential large-scale usage of the tables. Another grant, funded through a gift from the Roddenberry Foundation (led by alum Eugene "Rod" Roddenberry), is enabling Coupe to co-teach a class this spring semester with Visiting Assistant Professor of Applied Design Donna Cohn. That course focuses on the steps necessary to market and manufacture the table.

"What it is essentially is a surface that needs to be easily sanitized, stable, and comfortable," says Cohn. "And the reality is that people want the equipment to look like real medical equipment."

For both Ryan and Coupe, working on the project led to an interest in obstetrics and gynecology.

Ryan is currently completing the prerequisites for medical school at the University of Vermont. "I love science, and the combination of public health and patient care," she says, "but I'd never considered that I'd be capable of doing that until I worked on this project. It was hard, and self-directed, but working with the doctors showed me how much a simple intervention could matter."

She credits Hampshire with giving her the assistance and freedom to realize where her interests lie. "Hampshire gave me really good financial aid. I had some federal loans, but a huge grant from Hampshire was instrumental in my coming here," she said. "And the amount of support I got here was incredible. I never felt afraid to make a mistake, which I think is a great thing."

Coupe believes being involved in a real-world project while still an undergrad provided insights that couldn't have come in a classroom. It served as the basis of her Div III, Addressing Disparities in Women's Health Care: Redesigning a Portable Gynecological Exam Bed. Conlisk was her chair, and Cohn served on the committee.

"When you're in El Salvador," says Coupe, "it's so clear that the table is necessary. Doctors see it and say yes. Outreach screenings can take place in schools or public buildings where there aren't readily available exam surfaces. Doctors improvise examination surfaces using desks, tables, and sometimes personal beds. The table makes exams safer and more efficient, and women are more comfortable."

That sort of problem solving, says Conlisk, is why she chooses to teach at Hampshire. "As a faculty member, I'm most impressed by the students' perseverance," she says. "The design is just beautiful now. It's come a long way." Conlisk also appreciates the connections made between alums and current students through the exam-table project, as well as those made among various disciplines across campus: "There's really no reason why these classes would be focused on women's health in El Salvador. But this design work has meaning because it can be applied to clinical care in rural areas. It's a blend of health, design, and entrepreneurship."

Conlisk also appreciates the connections made between alums and current students through the exam-table project, as well as those made among various disciplines across campus: "There's really no reason why these classes would be focused on women's health in El Salvador. But this design work has meaning because it can be applied to clinical care in rural areas. It's a blend of health, design, and entrepreneurship."

As for Coupe, she believes it's an approach that can be seen throughout the Hampshire campus.

"It's not just about finishing your classes," she says. "You're doing a project because you care about it, and it's important to you. I've had access to these resources to create something real and physical, and I can't imagine doing this at any other school and having the kind of support I've had."