Of Mice and Mastocytosis

Sometimes a long journey begins at your doorstep.

When Avalon Mercado was choosing her Div III topic, she decided to research a rare disease that runs in her family: mastocytosis.

Her 32-page thesis, “The Effects of Antioxidants on P815 Mouse Mastocytoma Cells,” is both a scientific document and a highly personal one.”

“I worked building off the scientific literature,” Mercado says. “I sandwiched together two ideas that I think are cool: mast cells and the use of antioxidants as therapeutic agents.”

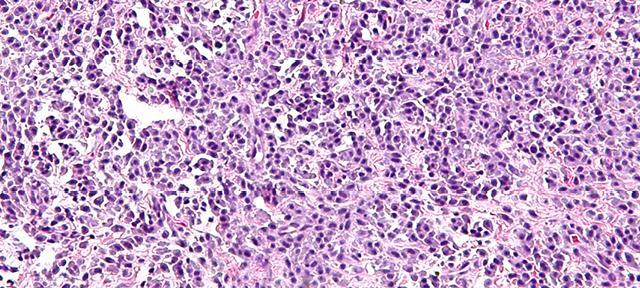

Mastocytosis is caused by a malfunction in mast cells, Mercado says, “which are immune cells responsible for allergic diseases.”

Allergies occur when the immune system goes into hyperdrive after exposure to a foreign substance, such as pollen or the venom from a bee sting. Mast cells trigger the body’s allergic response, which can range from minor symptoms, such as itchy eyes, to fatal ones, as with anaphylactic shock.

When mast cells mutate, they can accumulate in the skin, internal organs, bone marrow, or the small intestines, impairing their function.

The aggressive forms of mastocytosis are difficult to treat. In fact, most current therapies are more palliative than curative. In her research, Mercado wanted to see the role that antioxidants — naturally occurring molecules that can reduce cellular damage — play in the development and progression of mutated mast cells.

For her Div III, Mercado obtained a specific strain of mouse mastocytoma cells from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), a global bioresource center. She created a control group and an experimental group of the mouse cells to test her hypothesis that antioxidants could have a “rescue effect” on mutated mast cells. Her results showed that this is indeed possible.

She hopes her research will provide an avenue for the development of more-effective therapies for mastocytosis.

“There’s no one-size-fits-all treatment for mastocytosis; each case is handled individually,” Mercado says.

The inception of her Div III began early in her college career.

“I came to Hampshire thinking I would study zoology,” she says. “But during my first year I got involved in research in Hampshire’s bio lab, and I ended up doing genetics research. I’ve spent a lot of time in lab here.”

Mercado worked particularly closely with John Castorino, assistant professor of molecular biology in the School of Natural Sciences. He chaired her Div III committee; Rayane Moreira, associate professor of organic chemistry, was the other member.

She credits her committee with giving her invaluable guiding questions and, she says, “keeping me on track. John’s office was steps from where I was working, so I could check in with him all the time,” she says.

She also found help with the logistics of structuring her Div III at the Writing Center.

“I was able to spend so much time working in the lab because of the grants I received from Hampshire between fall 2017 and last summer,” Mercado says.

The School of Natural Science Student Funds support Division II and Division III research. Among them are the Tara Nelson Fund, the Sherman Fairchild Grant, the Denise O’Neill Fund, the Justine Salton Fund, and the Dr. Lucy Research Fund —all of which made awards to Mercado.

She graduated in May, and is now transitioning from the research world into the clinical world. “I’m jumping around between plans to go to grad school, medical school, or a physician’s assistant program,” she says.

Another possibility for a career? Genetic counseling. “It’s a budding field,” Mercado says, one that people with heritable diseases like mastocytosis find invaluable.