Psychology Professor Ethan Ludwin-Peery 09F Presents Big Findings in Uniquely Accessible Way

Visiting Assistant Professor of Psychology and Hampshire alum Ethan Ludwin-Peery copublished remarkable findings from original research about our near-universal tendency to envision how everything could be better instead of worse. Then he and his collaborator took the unusual step of ensuring that the information would be available to all.

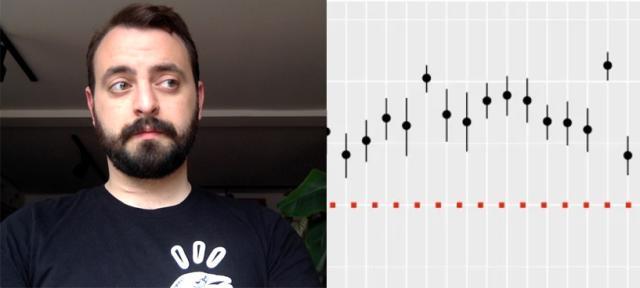

A recent article in Big Think delved into findings from studies conducted by Ludwin-Peery and his regular collaborator, Adam Mastroianni. Published in a paper titled “Things Could Be Better,” their curiosity in exploring a specific question — “Why do some things seem good and other things seem bad?” — elicited a discovery that made them change course. Assuming that value judgments were based on comparisons, what they actually found, says Ludwin-Peery, was that “when people imagine how things could be different, they almost always imagine how things could be better.”

“We didn't get an answer to the original question because we discovered this imagination bias instead,” Ludwin-Peery says, “but in some ways this discovery was even better. They say the most exciting phrase in science isn't ‘I found it!’ but ‘That's funny . . .’ so it was very cool to find something we didn’t expect.”

The other surprise to the researchers was the “almost always” part of their findings. “The result is also exciting because, as far as we can tell, the bias seems to be universal. This is really weird — in psychology, almost nothing is universal,” Ludwin-Peery says.

According to the paper, written in refreshingly plain language: “Most of what we discover in psychology is extremely contextual. Often, if you change the circumstances even a tiny bit, the effects change too. So far, this finding doesn’t seem to be like that. We can’t find a single thing that people, on average, imagine being worse. Nor have we found any group of people that doesn’t seem to do it. In psychology, this pretty much never happens.”

“Psychologists have looked around for about 150 years, finding individual effects that are mostly small and don't tell us a lot about how the mind really operates,” says Ludwin-Peery. “There are some big exceptions, but it’s rare we find something that could even plausibly be a fundamental law of psychology. Even if this new effect isn't fundamental, it’s still much more consistent than most psychological findings, which means it’s much more likely to be important in the long term.”

Ludwin-Peery and Mastroianni, a postdoctoral research scholar at Columbia Business School, also took an unusual approach to publishing their findings. Instead of in a top-tier psychological journal, which would have had paywalls and format requirements (read: would have to be written in a stodgy style suitable for curing insomnia), they chose to release them first as a blog post and preprint, making the documentation of their studies open-source, understandable, and entertaining.

“When the results started coming in, we realized we had a pretty big finding on our hands, and we talked about trying to submit the manuscript to Science (regarded by many people as the fanciest journal of them all),” Ludwin-Peery says. “Having a shot at getting published in a major journal should have been exciting. But when we sat down to try to write up our results in the standard academic format, we had a really hard time creating a manuscript we liked. We knew reviewers would expect us to pretend we had a theory that predicted this finding, even though we didn’t. And we knew the editors would reject it outright if we did things like make jokes in the paper, or admit we forgot why we ran Study 8. Basically, we found that we couldn’t write the paper without lying, and we really wanted to be honest. So that’s what we did instead.”

Working to make science more open, accessible, and diverse is something he and Mastroianni will continue to do. “It’s something I include in all my courses,” says Ludwin-Peery, “looking closely at academic science, its forms and expectations, who it lets in and who it keeps out, what kinds of behavior it encourages and what kinds it suppresses, and at alternatives that might be better. Science used to be much more open and accessible, and I think it can be open and accessible again.”