They Were a Force of Nature: Catching Up with the Unstoppable Aldersons

When you meet Glenna and Earl Alderson for the first time, you really wish you could hate them. They’re a living rebuke to middle-age lumpiness, undeniable proof that if you’d stuck to even a tenth of your New Year’s resolutions (to get outdoors, to switch from IPAs to seltzer, to just put on some sunscreen, for God’s sake), you, too — in your 50s — could look like you’re in the best shape of your life.

To make matters worse, the Aldersons are immediately likable. They exude the kind of cheerful levelheadedness that’s a prerequisite to, say, taking eight college kids, mostly city slickers, on a 15-day rafting trip on the Colorado River in the dead of winter, paddling up to 20 miles each day in the Grand Canyon through 40-degree whitewater.

“That was our second winter-term trip, and we were still in our twenties, but we were on duty with the students twenty-four/seven,” Glenna says. “If there’d been an emergency, the only way out was by helicopter. When we got back, everyone asked ‘How was your vacation?’ — that’s a question we get a lot.”

“There are always risks,” Earl adds, “but that’s how the students bond. They look out for each other.”

During the Colorado excursion, they were just warming up (figuratively speaking). That trip marked the onset of more than 560 weekend and extended trips — paddling, hiking, rock climbing, cross-country skiing, and mountain biking — led by the Aldersons during their 31-year careers as instructors in Outdoor Programs Recreation and Athletics (OPRA).

The duo were unstoppable. The Aldersons hauled students across the globe to plant Hampshire’s flag in Cuba, Greece, Spain, Mexico, Belize’s Silk Islands, Quebec, and even Kentucky, among dozens of other exotic locales. Pausing for breath, they’d head over to Deerfield or zip up Route 63 for some kayaking on the rivers in Deerfield and Millers Falls.

Ever on the hunt for new territory on land and sea, no whitewater, snowdrift, mountain, lava fall, or ice-faced cliff fazed them. They were a force of nature within nature, and they inspired their charges to similar fortitude.

“It’s about grace under pressure,” Earl says.

My husband and I are in business together, and I always remembered how Glenna and Earl managed themselves and their relationship in both personal and professional settings. They showed me how a couple who live can work together.

Gaia (Thurston-Shaine) Marrs 99F

That Hemingwayesque spirit perhaps shone brightest in students with serious physical challenges who nevertheless signed on for the Aldersons’ trips, knowing they would be both welcome and supported. “Absolutely courageous,” Glenna calls them, recalling one student who, she says, “used solar technology to charge the batteries that were essential for running his breathing treatments” in a remote area for days at a time. Another, Ross Newton 04F, had grown up kayaking, but a spinal-cord injury meant that instead of “hopping in a kayak,” he says, “I had to adapt things. Glenna and Earl were receptive to adaptive recreation, and while I was at Hampshire, I was able to get on the water.”

It was Earl’s relish for kayaking that first sparked the couple’s attraction to each other.

A Tennessee native, he spent a year as a visiting student at Oregon State University, in Corvallis, where he presented to a class a slideshow about kayaking. Glenna, a teaching assistant, fastened on the images of kayaks plunging off waterfalls and thought “I have to do that.” Earl offered to get her started. He had her at “Let’s roll a kayak.”

They became friends. Then he got her a job at Whitewater Limited, for which he led rafting and kayaking trips on the Chattooga River (where Deliverance was filmed). Romance blossomed after paddling season, when they went backpacking on the Appalachian Trail for a month. “I call that our first date,” Earl says.

They married in Columbia, Tennessee, in 1989.

In August 1987, when they were still dating, they joined a historic trip down the Katun River, in Siberia, with the organization Russians and Americans for Teamwork (Project RAFT), a kind of paddlers glasnost at the tail end of the Cold War and the first of their many activities with this group. During the journey, they stopped at villages on the river and remote towns bordering Mongolia.

At riverbank campsites, they kept meeting up with another guide, Bruce Conover 81F, who was in charge of navigating a team from National Geographic down the same river.

“The National Geographic trip was supposed to be the maiden voyage of Westerners on the river, but the RAFT people kept passing us and were a younger and cooler group,” Conover recalls. “I wanted to hang out with them at the campsites.”

Conover had signed on to teach kayaking at Hampshire that September but, passing through Moscow en route to Siberia, had wrangled a job as a cameraman at the CNN bureau there, working for Peter Arnett. (Conover, who had studied Russian in college and was fluent, stayed at the network’s Moscow bureau for 14 years, as part of a “go team” dispatched to cover the fall of the Berlin Wall, the student uprising in Tiananmen Square, and other breaking news.)

In Siberia, he recalls, he was in a “sticky situation and needed to find a last-minute replacement for the Hampshire job before he backed out of it. Hanging out with the RAFT group, he clocked Earl and Glenna doing what they do best: being “great with people,” he says, “and they were a tight couple, a good team. So I told them about the opening. There was a big kayaking scene around the Pioneer Valley and people would have killed for that job,” he says.

But that’s not the Alderson way. Instead, they waited for Conover to refer them and then hoped for a phone call from Hampshire inviting them to teach. The job seemed a step up from the seasonal guiding trips they’d been leading out West.

I was very lucky to be in Glenna’s advanced kayaking class with a small group of women. She constantly asked us to apply the skills we learned in the water to every facet of our life. She told us to lift our vision and look ahead, to have a goal and never stop struggling to reach it, whether that goal was an eddy in a rapid or an accomplishment academically.

Zoe Portman 08F

In late August, a hair’s breadth from orientation, Earl got a call, not to welcome him to the staff, exactly, but to offer a three-month contract for the fall term while Hampshire’s hiring committee for the job — which likely consisted of people who exercised by reaching for a book on a high shelf — conducted an exhaustive search for a permanent outdoors instructor for kids who didn’t identify as jocks.

“Start driving to Colorado and give us a call when you get there,” a voice on the other end of the phone instructed them. “We’ll let you know then if we can hire you.”

Earl got the gig — with a caveat. Hampshire wanted him on campus in two days to lead pre-orientation kayaking trips. When they arrived with their yellow Lab, Jed, Glenna and Earl found no available housing. No problem. They pitched a tent by a pond on campus.

“When it was cold at night, we took our sleeping bags into the office,” Earl says.

For three months, they adapted to the New England elements, making friends with the dogs — pets of students and faculty — that ran wild on campus. In December, life improved. The school offered both Earl and Glenna full-time jobs, and the Aldersons found a rental in Belchertown, just as their first Massachusetts winter set in.

They also took to the family feeling of the staff, faculty, and students.

Better yet, they realized they were in tune with the singular philosophy of Hampshire’s outdoors program: experiential physical education. This meant introducing students to new experiences, some scary like whitewater kayaking, in a supportive class that would enable students to get comfortable at every stage of their skill building. Patience is critical to this approach, and the Aldersons supplied that in abundance.

Earl and Glenna guided me in my time at Hampshire and have continued to be great friends and provide our family constant inspiration. Two of the biggest lessons I learned from them were [the importance of] loving the work you do and finding a way to give back to your community. The life lessons and friendship that Earl and Glenna give are priceless.

Matt Capozzi 93F

Hampshire’s kayaking program wasn’t always that chill. It was launched in 1972 by Jay Evans, who coached the U.S. Olympic kayaking team at Hampshire’s pool that year — the first (and last) time the school touched Olympic glory.

Evans’s focus on racing — fierce competition, pressure to perform, and exacting numerical evaluation — was antithetical to the school’s philosophy, yet somehow slipped under the radar. In Hampshire’s constitution, The New College Plan: A Proposal for a Major Departure in Higher Education (1958), the writers cautioned against “the building up of empires which results when particular [athletic] activities have their own buildings” encouraging only “[those] sports . . . which groups can play informally together.” (After decades of resistance, in 2011 Hampshire finally relented to the student demand for competitive sports and joined the United States Collegiate Athletic Association. It also joined the Yankee Small College Conference for varsity sports.)

The Aldersons admired Evans’s legacy but hewed to the far gentler experiential physical education philosophy. Soon the word spread around campus and across the other four colleges that Hampshire had some cool young instructors who wouldn’t bellow directions at them as they tried to right their kayak or dangled from a cliff face.

“The outdoors challen-ges are a metaphor for living,” says Glenna. “You learn how to weather adversity. I think about what we do as metaphors for navigating the adult life. You’re going down a river, and it’s calm, and then you tip over. How do you process risk? How do you process stress?”

On the van trips to trailheads, and lakes, and rock faces, the pair found that students wanted to know more than how to tell a clove hitch from a chock. They wanted to learn real-life stuff. How do you balance a checkbook? How do you decide whether to make your parents happy by going right into grad school after college or make yourself happy by hightailing it to Alaska to guide kayaking trips? How do you maintain a marriage? (The Aldersons’ answer: “Respect.”)

“I teach them about starting a 401K and a Roth IRA, and why they should do it young,” Earl says. (He recalled bumping into an alum who’d become a financial adviser and traced his success back to Earl’s van seminars.)

“We call the van ‘the mini classroom,’” Glenna says.

I went on a sixteen-day river trip with them in 1997 and spent time with Glenna, Earl, and their friends and family. I was a different person after that trip. When you’re running rapids with your friends and being afraid, and talking each other through your fears, it gives you energy to live the rest of your life.

Nate Connolly 93F

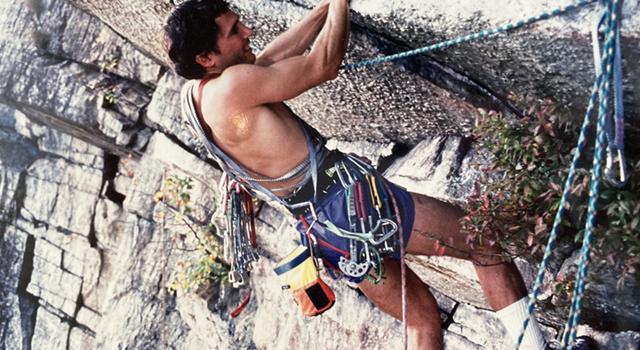

In addition to leading trips and American Red Cross first aid and CPR, the Aldersons teach several semester-long classes. Earl’s are ice climbing, Zen and the Art of Bicycle Maintenance, whitewater kayaking, and top rope–lead rope climbing. Glenna supervises the aquatics program, teaching swimming and lifeguarding. She instructs students in beginning and intermediate whitewater kayaking and cross-country skiing, too. To whip staff and faculty into shape, she leads open-community circuit-training sessions on campus and weekly hiking trips in the Pioneer Valley.

Off duty, the Aldersons made a name for themselves as athletes. Earl is widely admired as a whitewater rock star. Glenna was saluted as a “local crag legend” by the climbing blog Crux Crush and made the cover of the April/May 2014 issue of Climberism magazine.

Over the years, they didn’t seem to age, but their students grew up. The Alderson imprimatur inspired some of them to alchemize their avocation into a vocation. Gaia (Thurston-Shaine) Marrs 99F, for example, returned to her native Alaska and now owns three outdoors-adventure businesses there: St. Elias Alpine Guides (hiking and backpacking); Copper Oar (single and multiday rafting trips); and Pangaea Adventures (kayaking). Another alum, Matt Capozzi 93F, signed on with Burton Snowboards after graduation, moved onto footwear companies, among them Nike, and then cofounded North Drinkware, a Portland-based company that handcrafts crystalline miniatures of mountain ranges rising within tumblers and pints.

One of many former students across the country with whom they became friends, Nate Connolly 93F, headed to Bend, Oregon — a former logging town on the eastern edge of the Cascade Mountains — and, after a few years banging nails, founded Ridgeline Custom Homes, for which he’s the designer and lead carpenter.

“Once we realized we could afford to retire, we started visiting places that appealed to us,” Glenna says. “Matt Capozzi’s parents had a house in Bend because Matt and Nate are close friends, and they said, ‘After all you’ve done for Matt, feel free to stay at our home,’ so we lived there for a month this past summer” testing out Bend as a future home.

Nate is now building the Aldersons a Craftsman-style house there, not far from his home. They’re aiming to move there in December.

Glenna explains their plans to leave their jobs of three decades, pull up stakes, and move across the country in Alderson-ese: “It’s the next adventure.”

From the fall 2018 Non Satis Scire magazine