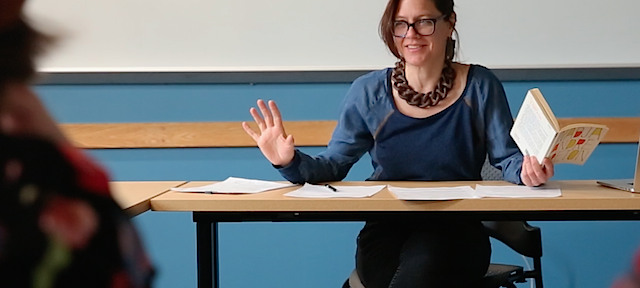

New Faculty Q&A with Jennifer Bajorek

Hampshire fourth-year student Emily Lawson gets to know one of the College’s newly appointed faculty members, Jennifer Bajorek, who earned her PhD in comparative literature at the University of California Irvine and followed that with a postdoc in the rhetoric department at Berkeley. Before Hampshire, she taught at Goldsmiths, University of London.

Emily: First, a classic icebreaker. What’s a fun fact about you?

Jennifer: I can ride a motorcycle in high heels. That comes from my research in Cotonou, Benin. You have to ride a motorcycle, and you have to wear high heels. I can even get off a moving motorcycle in heels.

Emily: That’s a great answer. My next question is very, very hard. What are five books that changed your life?

Jennifer: Oh my God—that is a hard question! I can’t say twenty? Okay, thinking about what’s available in English and deliberately excluding books I’ve written about:

- Kathy Acker, Great Expectations

- Georges Bataille, Manet

- Édouard Glissant, Faulkner, Mississippi

- Anything/everything by Fred Moten (his theory, work as a public intellectual, poetry)

- Gertrude Stein, How to Write

Emily: Can you tell me about your own books?

Jennifer: The book I’m working on now is on photography in the mid-twentieth century in West Africa. I try to complicate Western and Northern histories of photography by bringing in material from Senegal and Benin. I did fieldwork and interviews with photographers and their families, collectors, and politicians who were amassing photographic collections around their careers in the late fifties and early sixties. In the book, I make theoretical arguments about the role played by photography in the process of decolonization. I also try to demystify the contemporary mania for so-called African photography. By design, it’s very interdisciplinary.

Emily: Can you tell me about your first book?

Jennifer: My first book was on the relationship between irony and capital in Marx and Baudelaire. I took an idea that’s closely associated with literature and literary theory — irony — and confronted it with a concept from political economy. Like my book on photography, this is a book about art and politics, but it’s framed by Marxism rather than postcoloniality.

Emily: After doing all this work in interdisciplinary studies, how is it at Hampshire where people kind of, well, start there?

Jennifer: I feel really at home here. I feel this intense kinship with all Hampshire students because I’m always already doing these interdisciplinary things. I’m immediately thrilled, and I embrace the challenges of their projects. Maybe you can tell me: how can faculty give students a deeper understanding of what it means to do interdisciplinary research earlier on?

Emily: Honestly, I wish I’d understood how to get the most out of the library catalogue. I didn’t realize how deep it could take me. You can follow chains of information forever. I also wish I’d known that I can actually contact libraries and archivists directly if I’m stuck. If you told me, at eighteen, “You can e-mail these professors and authors and get any information you need,” it would have opened up a lot.

Jennifer: So, breaking down the barriers that exist when students don’t realize they can tap into the expertise of other people.

Emily: Right. To turn that around, what’s some advice you have for new undergraduate students?

Jennifer: I’ve found that my first-year students feel very free in discussion but feel much more confined in their writing. I’ve been encouraging them to start with a question they know they can’t answer rather than a question they know they can.

Emily: What’s a subject in your field that still needs to be explored?

Jennifer: In literary and cultural theory, there’s so much happening at the intersection with digital culture and so much to explore in terms of the new ways in which writing, texts, images, and visual objects are circulating. I’m not a fan of hype about digital revolutions, but we’ve barely begun in terms of thinking about new spaces and forms of creative and cultural practice in digital spaces. There’s a lot happening in contemporary culture that the more classically critical and theoretical disciplines haven’t yet caught up with.

In political and social theory, there’s a huge wave of interesting work just starting to gain momentum, and a younger generation — your generation — is trying to adapt the theoretical and analytical tools of earlier thinkers, the tools of Left social theory, to the contemporary situation.

Many of my students are thinking about literature, art, and culture in relation to the desire for social and political change, so I think we’re about to see a revolution in this field, which is not one field in the conventional sense.

Relevant to my photography research in Africa, there’s an area I want to mention that may sound small, but it’s actually really important. All over West Africa, where you have this rich photo history, people are in the midst of digitizing historical and archival collections — like everyone else all over the world. People are digitizing, but they’re not capturing meaningful metadata. This means there are practical questions but also more theoretical ones to explore in terms of how to develop meaningful metadata in a digitization project in the South and in a postcolonial environment, where the protocols developed by commercial actors focused on northern markets don’t apply. This is a huge, unexplored question.

Emily: And, of course, if you don’t have the metadata, then nobody can find the material at all.

Jennifer: Exactly. It’s critical. And this problem is at the intersection of all these different fields. To address it properly, you have to bring people working on photography and on cultural and intellectual histories in environments that don’t look like ours in terms of digital infrastructure and academic infrastructure, together with technical people, people who can write code and do metadata design and think about digital archives at a technical level. It presents new opportunities to produce knowledge and raises new questions about cultural politics.

Emily: When you were an undergraduate, is this where you thought you’d be?

Jennifer: A college professor? Not necessarily. Thinking and talking about these kinds of things? Definitely.