Hampshire Mourns the Loss of Founding Faculty Member Bill Marsh, a Father of the College's School of Cognitive Science

The College was saddened to learn of the death of mathematical logician and educational visionary William (Bill) Marsh, who joined the faculty in 1969 and was instrumental in developing Hampshire's School of Language and Communication, which evolved into the School of Cognitive Science.

In the initial planning of Hampshire, in the 1960s, among other curricular innovations that have been mainstays of the College — narrative evaluations, student-designed courses of study, and the Div III final-project requirement — was the organizational principle of broad interdisciplinary “schools” rather than narrowly defined traditional academic departments.

Hampshire’s first president, Franklin Patterson, agreed to three logical categories for these schools: Humanities & the Arts, Social Sciences, and Natural Sciences & Math. Less predictable was his desire to add a school for Language Studies, a somewhat confusing moniker, as his intention was for it to encompass linguistics, mathematics, analytic philosophy, cognitive psychology, psycholinguistics, and information sciences.

Two young math logicians, one of whom was Bill Marsh, applied for and were hired into faculty positions within the proposed school. But the concept was so new and untried that the College didn’t actually open with this fourth school; instead, Assistant Professor Marsh taught in the School of NS/M while he and a group of other curious faculty members explored the possibilities of Patterson’s fourth category of inquiry.

“This group was diverse in particular intellectual backgrounds and personality, yet also united in its commitment to reforming undergraduate education . . . and forging a new approach to mind, meaning, and communication,” writes Professor Emeritus of Psychology Neil Stilling in “A History of the School of Cognitive Sciences at Hampshire College, 2021.”

“Any fool knows that mathematics is a science and therefore should be put in with physics and biology just as it was when we were at Old Siwash,” wrote Marsh, with humor, in “A Proposal for a School of Language and Communication at Hampshire College,” submitted in April 1972. “However, this defense of what has been academic common sense has some serious flaws, and recent history presents some reasons for changing our views.”

Ultimately, a Language and Communications “program” was announced in the fall 1970 course guide, but the first official course offerings were in spring 1971. The program was elevated to the School of Language and Communication in 1972.

“Bill had a searing intelligence and a passion for his work.”— Penina Glazer

“Bill and his colleagues were committed to the radical idea that the intersections of computer science, philosophy, and linguistics could be taught to undergraduates,” said retired, long-term faculty member and former acting president Penina Glazer. “They turned out to be right, and Hampshire graduates went on to do distinguished work in these fields. Bill had a searing intelligence and a passion for his work.”

Writes Stillings, “The term cognitive science was coined in the mid-1970s, . . . and clearly fit the interests of the School’s faculty and its curriculum better than language. After waiting a couple of years to make sure the term was taking hold, the School changed its name to Communications and Cognitive Science in 1983–1984.”

Hampshire’s School of Cognitive Science (CS) was the first of its kind in the country, and played a big part in the development of the study of cognitive science overall. The CS faculty wrote the first comprehensive textbook in cognitive science (Stillings et al.,1987). CS organized national workshops on cognitive science education funded by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the National Science Foundation. And CS created possibly the first ever undergraduate EEG laboratory for research on cognitive processes using event-related brain potentials (ERP).

“In a significant sense, I owe my career to him,” remembered Stillings, who was hired by Marsh, “and I have long been disappointed that I was not able to spend more of it with him, as he left Hampshire many years before me. Teaching, and, more broadly, exploring ideas with students, was Bill’s vocation, his calling. . . . Bill saw connections across fields that others failed to see.”

Like Hampshire itself, CS continued to shape-shift around changes occurring in the world, institutional adjustments, and its own intellectual goals. Over the years, the disciplinary composition of its faculty changed, as did its name, ultimately becoming simply Cognitive Science. In 2019, all of the College’s schools were disbanded in favor of unbounded learning without subdivisions, encouraging students to engage with pressing global issues requiring multidisciplinary thinking and skills.

“The obvious pleasure he took in arguing mathematical theory (not with me, I’m afraid) matched his passion to understand how students constructed their mathematical understanding of the world,” said Professor Emerita of Biology Merle Bruno. “I always think of him as a joyful, playful intellectual.”

Bill Marsh earned his B.A. and Ph.D. in mathematics from Dartmouth College. Inspired by the civil rights movement, he went on to a three-year stint at Talladega College, a historically Black institution (HBCU) in Alabama, before arriving at Hampshire, where he taught until 1985. Per his obituary, Bill “later taught classes at various schools and colleges until his retirement. He was instrumental in bringing Blockfest, an early mathematical education program for children and parents, to the Olympic Peninsula.”

William Ernst Marsh passed away on January 24, 2023, at the age of 83.

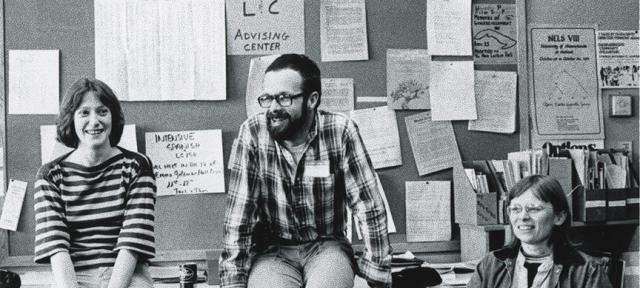

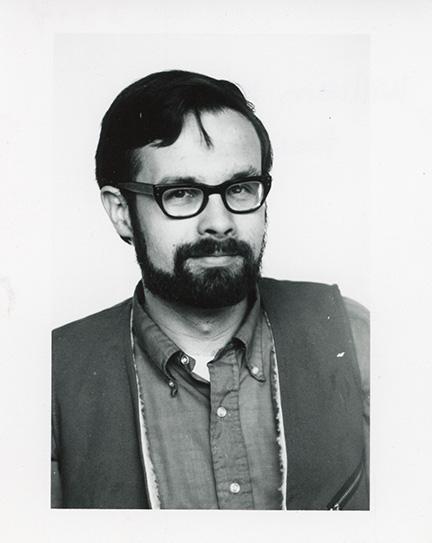

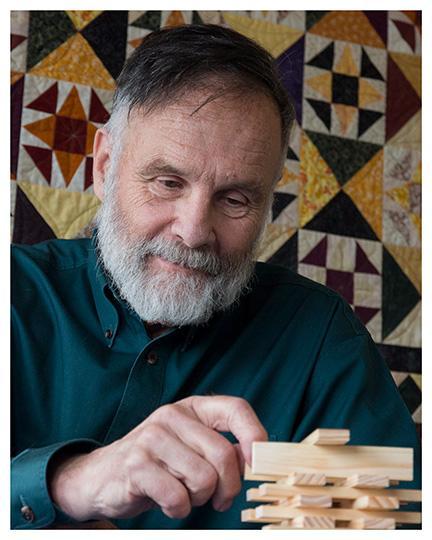

Photos (top to bottom):

- Marsh with former faculty member Janet Tallman (right) and an unknown student (left), 1978. Courtesy of Hampshire College Archives.

- Head shot of Marsh, 1974. Courtesy of Hampshire College Archives.

- Marsh with a child, 1986. Courtesy of Hampshire College Archives.

- “Real Numbers,” a portrait by Neil Stillings, 2016, from a photography project titled Guys I Know: A celebration and reflection on male friendship.

“He suggested two elements that embodied his life and interests,” wrote Stillings. “The first was the quilt in the background, which reflected his love of pattern and the importance of visual thinking in his mathematical work. The second was the block structure, which represented his commitment in his retirement years to using play, construction, and problem solving with physical objects as a way of teaching mathematical concepts to young children.”