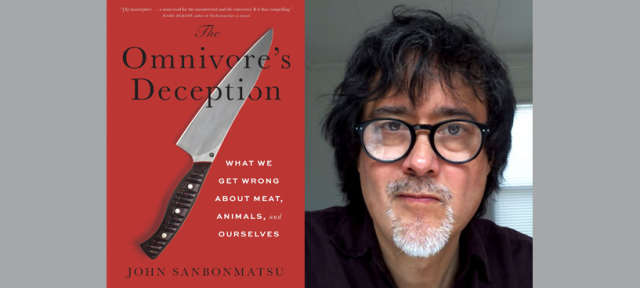

Hampshire Alum John Sanbonmatsu 80F Publishes Book on the Ethics of Eating Meat

John Sanbonmatsu 80F discusses how anti-nuke activism at Hampshire set the stage for a lifetime of questioning harmful ideologies and led to his groundbreaking research and scholarship within the field of critical animal studies.

How did Hampshire inspire your early activism?

It was Hampshire that introduced me to the importance of bearing witness to, and speaking out against, injustice. When I first arrived at the College, I set out to study creative writing. However, in the early 1980s, I got swept up in the Nuclear Freeze campaign, which sought a moratorium on the United States–Soviet nuclear arms race. Hampshire students, led by Chuck Collins 79F and Matthew Goodman 79F, organized the first intercollegiate conference on the campaign.

I and about 40 other students ended up occupying the Cole Science Center to pressure the Trustees to divest the College from the top nuclear weapons–producing corporations. Eventually, the Trustees agreed to discuss our proposal at an open meeting in exchange for our ending the occupation. We agreed, and the Trustees voted to divest.

And how did this activism influence your scholarship?

My involvement in the freeze campaign led me to a Div II on the history of the nuclear arms race and a Div III called “Soviet Strategic Nuclear Weapons Policy.” Professors Carollee Bengelsdorf and Margaret Cerullo in particular opened my eyes to the nature of ideology and political power. It was at Hampshire that I came to understand the pervasive nature of social injustice and to appreciate the role of ideology in shaping our conceptions of the world. People can be influenced by quite dangerous ideas that make us simply unwilling to question imperialism or see when moral stakes are involved.

Why critical animal studies?

While I was a student, I first read Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation, which convinced me to become a vegetarian and then a vegan. However, at that time, our treatment of nonhuman animals was still being treated as a “personal" moral imperative — that is, something we each had to grapple with as a consumer of meat and other animal products. Over time, however, my training in sociology and political science led me to question the more fundamental structures of power and inequality that lie at the basis of the animal food economy. As a consequence, a major strand of my scholarly research has been on the social, political, and even existential dimensions of the animal system. My second book, Critical Theory and Animal Liberation, was an edited anthology highlighting the ways our violent exploitation of other animals intersects with other forms of power and authority, including capitalism and patriarchy. The book has since become one of the touchstone works in the interdisciplinary field of critical animal studies.

What’s the key theme of The Omnivore’s Deception?

At the heart of my new book is my claim that our oppression and mass violence against all the other beings of the Earth is the fundamental basis of human society and identity. In The Omnivore’s Deception, I show how the recent discourse on “enlightened omnivorism,” championed by Michael Pollan, Barbara Kingsolver, Temple Grandin, and other critics, has deceived members of the public into thinking they can have their conscience and their meat too. But I show why “compassionate” and “sustainable” meat is in fact a contradiction in terms.

I owe these and other insights to the political milieu I was immersed in at Hampshire. Introduced to the “critical” tradition in social and political thought, I learned to place questions of justice at the center of my later personal and professional choices. No part of justice, I argue, can excuse the domination or killing of other sensitive beings.